Useful information

Driving time

55 min

Distance

73.8 km

Nestled on the right bank of the Rance, Saint-Suliac is one of the most beautiful villages in France, a true Breton gem where stones steeped in history, ancestral myths, and a gentle way of life mingle. This seaside village, seemingly frozen in time, invites you to discover its rich heritage, its picturesque streets, its astonishing legends, and its breathtaking views of the Rance estuary.

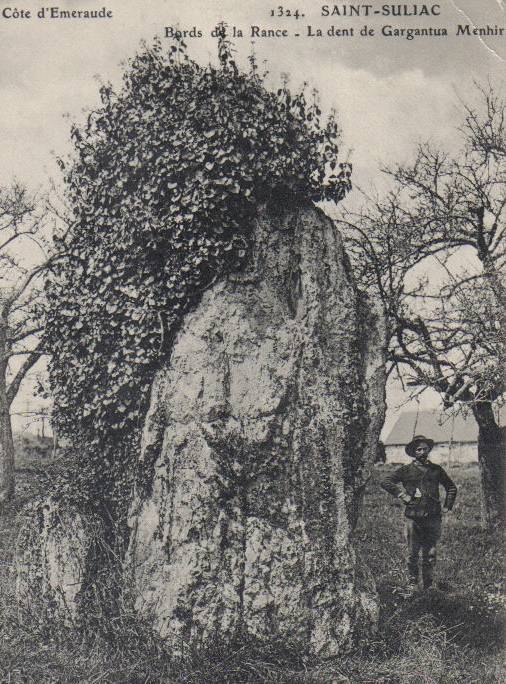

The menhir of Chablé or the Tooth of Gargantua

On the heights of Saint-Suliac, erected on private land in the place called Chablé, stands an impressive five-meter-high white quartz stone: the Chablé menhir, also called Gargantua's Tooth. It is one of the rare prehistoric remains still visible in the commune.

This megalith is not the only one to bear witness to the region's ancient past. Other lost structures are also mentioned, such as the Gargantua gravel, another broken menhir, and three dolmens: the Pierre Couvretière, the Mont Garrot dolmen, and the Vigneux cove dolmen, also known as the Bed or Cradle of Gargantua, destroyed in 1850.

The legend of Gargantua in Saint-Suliac

As is often the case in Brittany, these monumental stones are surrounded by fantastical tales. In Saint-Suliac, the giant Gargantua, well-known in popular tradition, is said to have met his death here, struck by a curse. Born near Saint-Malo, he is said to have attempted a heinous act: devouring his own son, like the Titan Cronus in Greek mythology.

Outraged witnesses intervened in time and substituted a rock for the child. By closing his jaws on the stone, the giant lost a tooth, now embedded in the ground as Gargantua's Tooth. But in his blind rage, he accidentally struck his son with a fatal blow. Consumed by remorse and harassed by the locals, he wasted away and died a year later. He was buried on what became Mont Garrot, formed, according to legend, by the collapse of a cliff whose earth covered the body of the giant folded in seven. His son, meanwhile, was buried at the site of the tragedy, beneath the famous stone tooth.

The Viking camp at Anse du Vigneux

At low tide, in the Vigneux cove, attentive walkers can spot the foundations of what is known as the Viking camp. This enigmatic site, discovered on the public maritime domain, is considered to be an ancient fortified camp established by the Normans, perhaps on the remains of an ancient Roman castrum.

Occupied between 900 and 950, this camp must have consisted of a promontory of land fortified with wood, protected by a collection of stones, with possible access for longships. The immediate proximity of the sea or a river was essential for these feared sailors, who, despite their adoption of the horse, remained deeply attached to the coast.

Traces of their presence can be found elsewhere in Brittany, notably in the regions of Dol and Saint-Brieuc, where Danish communities temporarily settled. These incursions were facilitated by the hasty departure of religious and secular elites, leaving the countryside defenseless against invaders.

The oratory of the Virgin of Grainfolet

Overlooking the village and the port, the oratory of the Virgin of Grainfolet is a moving place of remembrance, erected in homage to the Newfoundlanders, those courageous sailors who went fishing for cod on the banks of Newfoundland.

In 1874, a particularly perilous fishing trip prompted a collective wish: if all the sailors returned safely, a shrine would be built in thanks. It took twenty years, but in 1894, all the fishermen returned alive. The shrine was then built on the very spot where their wives once watched the horizon, hoping to glimpse the ships' sails.

A family walk with the Adventure Notebooks

Saint-Suliac also offers a fun way to discover its heritage: the Adventure Books, a small booklet designed for children and their families. Accompanied by Tom and Lola, young visitors can explore the village's streets and monuments while having fun.

The booklet is available at the Tourist Information Office, located on Place du Carrouge, in the town hall annex. In summer, the office is open every day, with a friendly team—Marine, Philomène, and Maëlane—ready to welcome you and guide you through your visit.

A thousand-year-old history

Saint-Suliac is an ancient commune, once formed around a peninsula surrounded by the waters of the Rance, notably by an arm called the Bras de Châteauneuf. Until 1850, its territory also included that of Ville-es-Nonais, today a neighboring commune.

Its relief is remarkable: the amphitheater-shaped village is framed by the point of Grainfolet to the north and that of Mont Garrot to the south. From the latter, the view extends over the Rance and its natural wonders. This same mountain also contains traces of ancient settlements and the famous Viking camp mentioned above.

The village is also linked to the figure of the Welsh monk Saint-Suliac, who came to settle here in the 6th century. He is said to have founded a monastery, the ancestor of the present-day town, and to have died here in the year 606, at the age of 76. Tradition has it that his remains rest at the bottom of the nave of the church.

The church and the alleys of the village

The original monastery has disappeared, but a church was rebuilt in the 12th century, before being entrusted to the Abbey of Saint-Florent de Saumur, which established a priory there. The church suffered extensive damage over the centuries, particularly during clashes between the Bretons and the Normans, and then during the Wars of the League.

In 1597, Henry IV's troops attacked Saint-Suliac, where 250 supporters of the Duke of Mercoeur had taken refuge. The church spire and turret were destroyed, and the village was besieged. The village's current houses date mostly from the 17th century, rebuilt around the church after the conflict.

The village has changed little since the 1809 land registry. A main street leads down to the port, lined with narrow, charming, flower-filled lanes, with stone walls that conceal gardens. This network of alleyways contributes greatly to Saint-Suliac's unique identity.

A traditional and marine economy

Until the 19th century, Saint-Suliac lived mainly from the sea. The 1851 census shows a majority of sailors, some embarking for the deep-sea fishing. There were also a few salt workers and weavers. The textile industry, once flourishing, was then in decline, as was salt production, which continued until 1880.

According to Elvire de Cerny, author of a reference work on the village, the land was often cultivated by women while the men were at sea. Most households owned a house, a garden, and a few farms. This simple but balanced way of life lasted until the mid-20th century.

Saint-Suliac today

Unlike other coastal villages, Saint-Suliac has long retained its maritime character. It was only recently that it opened up to tourism. Today, the pleasures of sailing, shellfish gathering, hiking trails, and birdwatching have replaced traditional activities.

Regattas are still held here, and visitors flock to enjoy the peace, natural beauty, and timeless atmosphere of this listed village. It is one of the rare places where legends, history, heritage, and nature intertwine so harmoniously.

Conclusion :

Saint-Suliac isn't just a pretty Breton setting: it's a vibrant village, rich in history, legends, and its inhabitants. Whether you're a history buff, a lover of bucolic walks, or simply curious about authenticity, this little corner of the Rance will charm you.